Dec 2, 2025

ERC-4337 Paymasters: Better UX, Hidden Risks

ERC-4337 paymasters unlock powerful UX by abstracting gas costs, but they also add complexity and subtle bugs. Explore some common pitfalls in real-world implementations and learn how to design production-ready paymasters.

Introduction

ERC-4337 (Account Abstraction) has unlocked a new wave of UX improvements for Ethereum. By decoupling users from EOAs (Externally Owned Accounts), it enables smart contract wallets, gas sponsorships, and flexible authentication mechanisms.

One of the most powerful features introduced by ERC-4337 is the paymaster, a contract that can sponsor gas fees for users. This allows dApps to deliver seamless, “gasless” experiences where users don’t have to hold ETH to transact.

However, building a correct paymaster isn’t trivial. We’ve seen many developers trip up on subtle details of the standard, which can cause unexpected behavior or unnecessary complexity.

In this article, we’ll break down how ERC-4337 works at a high level, zoom in on the paymaster’s role, and walk through the most common pitfalls we’ve observed when implementing paymasters. By the end, you’ll have a clear picture of how to design paymasters that follow best practices and are production-ready.

ERC4337 Overview

Traditional EOAs vs Smart Contract Wallets

In Ethereum’s early design, user accounts are Externally Owned Accounts (EOAs), controlled by a private key. When you send a transaction (e.g. token transfer or contract call), your private key signs the transaction, and you must pay gas in ETH. If the key is lost or stolen, you lose access to everything permanently. This setup is simple, but also rigid and risky.

By contrast, smart contract accounts (or "smart wallets") are programmable. They can enforce logic like multiple signatures, spending limits, social recovery, batching, and more, automating many aspects of security and usability.

Why ERC‑4337 Was Introduced

Smart wallets offer powerful features, but Ethereum’s protocol restricts transactions to originate only from EOAs. Previous proposals (e.g. EIP‑2938, EIP‑3074) tried to change the protocol itself, requiring a hard fork. ERC‑4337 achieves account abstraction entirely off‑chain, using higher-layer infrastructure without any changes to Ethereum’s consensus layer. This unlocks key UX improvements:

- User recovery for lost keys (e.g. social recovery)

- Batched or atomic multi-step operations in one flow

- Paying gas fees with ERC‑20 tokens or via sponsor (gasless UX)

- Using custom signature schemes or multisig logic

- Creation and use of smart contract wallets without needing ETH or seed phrase upfront

How ERC-4337 Works

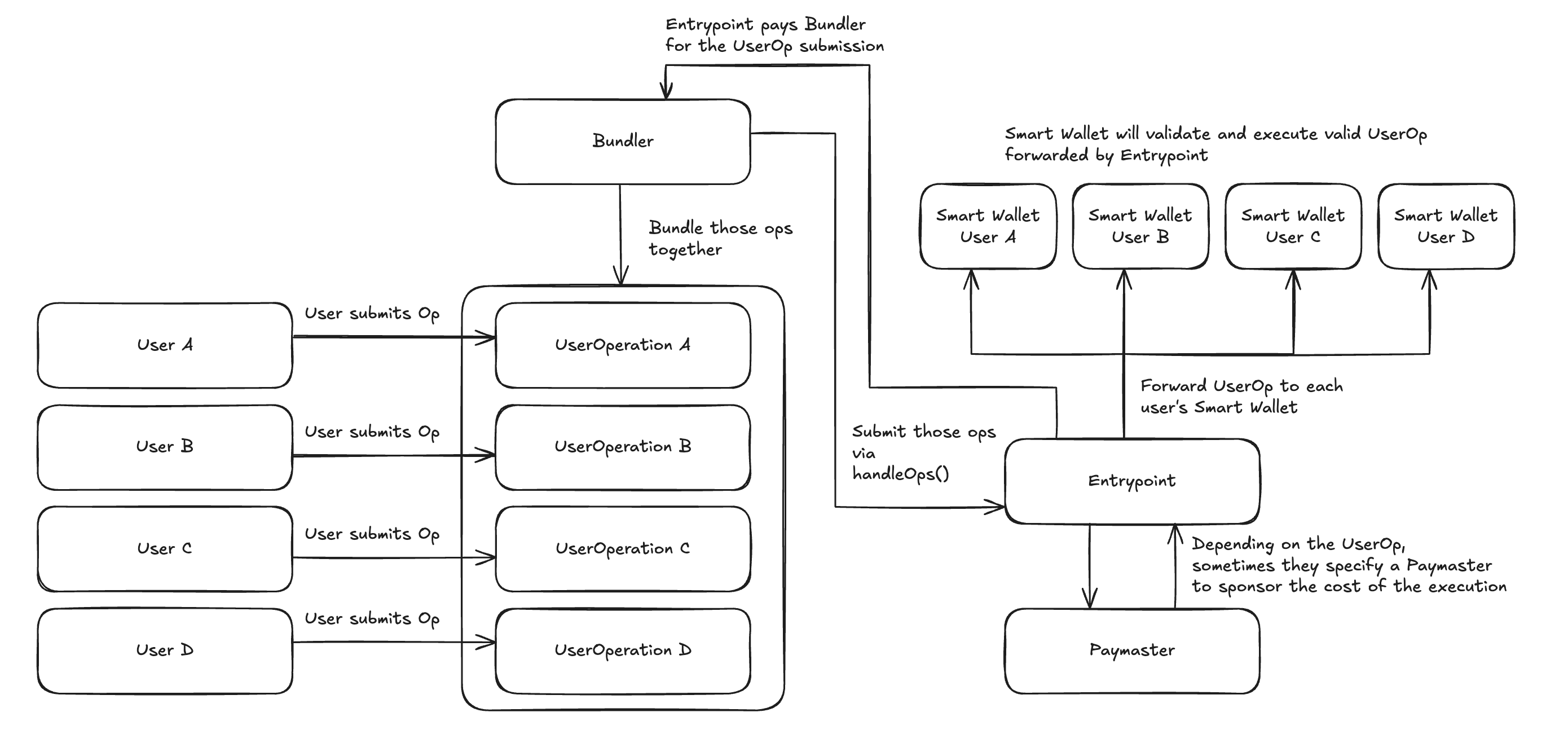

Before diving into each component, let's look at how ERC-4337 works at a high level:

The diagram above shows the key flow of ERC-4337. Below is a short explanation of each component shown above.

UserOperation

A UserOperation is a pseudo‑transaction object representing the user’s intent. It includes data like:

- Target contract call(s)

- Signature or validation metadata

- Gas limits and fee payment details (wallet address, paymaster, bundler)

UserOperationsare submitted to a separate mempool (often called alt‑mempool), not the regular Ethereum transaction pool.

Smart Contract Account

Often called Sender or Smart Account, this is a user-controlled contract implementing logic via validateUserOp() and executeUserOp(). It specifies custom rules: signature checking, nonce logic, allowed calls, or spending limits.

Bundler

A Bundler is an off‑chain service or node monitoring the alt‑mempool. It collects multiple UserOperations, packages them, and submits them in a single transaction to the EntryPoint contract. Bundlers must use an EOA to pay gas upfront and are later reimbursed.

EntryPoint

The EntryPoint contract acts as the central on-chain gateway for ERC-4337. For every batch of UserOperations submitted by a Bundler, the EntryPoint validates and routes each operation back to the corresponding Smart Contract Wallet for execution.

Once all operations have been processed, the EntryPoint calculates the total gas consumed and reimburses the Bundler. This payment can come either directly from the sender's Smart Account deposit in the EntryPoint or from a paymaster that has agreed to sponsor the transaction.

Paymaster

A paymaster is an optional smart contract that enables flexible gas payment options. It can either sponsor gas fees directly or allow users to pay gas using ERC-20 tokens instead of ETH. It runs two key functions:

validatePaymasterUserOp()to validate the operation. This can check sponsorship eligibility or verify that the user has sufficient ERC-20 token balance and allowance to cover gas costs. The exact implementation of the function depends on how the protocol implements it.postOp(), which handles post-execution accounting. For sponsored transactions, this may update internal accounting records, while for token payments, it typically finalizes any accounting related to the ERC-20 token payment.

By supporting both sponsorship and token-based gas payments, paymaster removes the requirement for users to hold ETH, enabling truly gasless transactions through either model.

Understanding the EntryPoint's Flow

When a bundler submits UserOperations to the EntryPoint contract via handleOps(), the processing occurs in two main phases: Validation and Execution.

Validation Phase

In this phase, the EntryPoint first validates all operations in the submitted UserOps array before executing any of them. This ensures that only valid operations proceed to execution. For each UserOp, the EntryPoint:

- Calculates the required prefund amount by summing up all specified gas limits (verification, execution, and paymaster if used) multiplied by the user's specified

maxFeePerGas - Calls

validateUserOp()on the sender's smart account contract to verify the operation's validity (e.g. checking signatures) - If no paymaster is specified, attempts to deduct the prefund amount from the sender's ETH deposit in the

EntryPoint(this can be partially refunded later if actual execution costs less) - Validates the nonce to prevent replay attacks

- If a paymaster is specified, it will deduct the required prefund amount from the paymaster's deposited ETH and then call

validatePaymasterUserOp()on the paymaster contract to verify it will cover gas costs

Only after all these validation checks pass will the EntryPoint move on to actually executing the UserOperation. This strict validation flow ensures that:

- The operation is legitimate and authorized by the user

- Sufficient funds are available to cover gas (either from user or paymaster)

- The operation cannot be replayed

- All involved contracts (sender and paymaster) have approved the execution

This multi-layered validation approach is crucial for maintaining security when processing operations that can involve complex smart account logic and third-party gas sponsorship.

Execution Phase

After all operations have passed validation, the EntryPoint begins the execution phase, processing each UserOperation individually. For each operation, the flow is:

- The

EntryPointmakes a call toinnerHandleOp(), which:- Forwards the operation to the sender's smart account contract

- Executes the intended transaction(s) within the smart account

- Handles post-execution tasks and cleanup

- If a paymaster was used,

Entrypointwill callpaymaster.postOp()to:- Allow paymaster to finalize its accounting

- Process any refunds or additional charges

- Complete any paymaster-specific logic

- Finally, after all operations are processed, the

EntryPointcompensates the bundler for:- Gas costs from executing all operations

- Overhead from submitting the batch transaction

- Any unused gas, which is refunded

This execution flow ensures secure and atomic operation execution, accurate tracking and settlement of gas costs, support for custom paymaster payment logic, and proper compensation for bundlers who provide the transaction submission service.

Now that we understand how the EntryPoint works at a high level, let's examine how some protocols have failed to properly implement paymasters that align with the EntryPoint's execution model, leading to potential vulnerabilities.

Common Pitfalls in Paymaster Implementation

While paymasters offer powerful flexibility, they also introduce new complexity, and with it, room for subtle bugs. Missteps in paymaster design can not only break gas sponsorship flows, but also expose their deposited ETH in the EntryPoint to exploitation or griefing.

In this section, we’ll walk through the two most common pitfalls we’ve observed in real-world paymaster implementations:

Undercalculated Gas Costs

To understand this issue, let's first examine how gas penalties work in the EntryPoint. When a UserOperation specifies an execution gas limit higher than what's actually used during execution, the EntryPoint charges a penalty of 10% of the unused gas. This penalty is paid to the bundler and is deducted from either the user's deposit (for regular transactions) or the paymaster's deposit (when using a paymaster).

Now, let's examine a real-world example of how this penalty mechanism could impact paymasters. The SEND Protocol's paymaster implementation provides an instructive case study:

contract TokenPaymaster is BasePaymaster, UniswapHelper, OracleHelper {

[...]

function _validatePaymasterUserOp(PackedUserOperation calldata userOp, bytes32, uint256 requiredPreFund)

internal

override

returns (bytes memory context, uint256 validationResult)

{

unchecked {

uint256 priceMarkup = tokenPaymasterConfig.priceMarkup;

uint256 baseFee = tokenPaymasterConfig.baseFee;

uint256 dataLength = userOp.paymasterAndData.length - PAYMASTER_DATA_OFFSET;

require(dataLength == 0 || dataLength == 32, "TPM: invalid data length");

uint256 maxFeePerGas = userOp.unpackMaxFeePerGas();

uint256 refundPostopCost = tokenPaymasterConfig.refundPostopCost;

require(refundPostopCost < userOp.unpackPostOpGasLimit(), "TPM: postOpGasLimit too low");

uint256 preChargeNative = requiredPreFund + (refundPostopCost * maxFeePerGas);

// note: price is in native-asset-per-token increasing it means dividing it by markup

uint256 cachedPriceWithMarkup = cachedPrice * DENOM / priceMarkup;

if (dataLength == 32) {

uint256 clientSuppliedPrice =

uint256(bytes32(userOp.paymasterAndData[PAYMASTER_DATA_OFFSET:PAYMASTER_DATA_OFFSET + 32]));

if (clientSuppliedPrice < cachedPriceWithMarkup) {

// note: smaller number means 'more native asset per token'

cachedPriceWithMarkup = clientSuppliedPrice;

}

}

uint256 tokenAmount = weiToToken(preChargeNative, cachedPriceWithMarkup);

tokenAmount += baseFee;

SafeERC20.safeTransferFrom(token, userOp.sender, address(this), tokenAmount);

context = abi.encode(tokenAmount, userOp.sender);

validationResult =

_packValidationData(false, uint48(cachedPriceTimestamp + tokenPaymasterConfig.priceMaxAge), 0);

}

}

[...]

function _postOp(PostOpMode, bytes calldata context, uint256 actualGasCost, uint256 actualUserOpFeePerGas)

internal

override

{

unchecked {

uint256 priceMarkup = tokenPaymasterConfig.priceMarkup;

uint256 baseFee = tokenPaymasterConfig.baseFee;

(uint256 preCharge, address userOpSender) = abi.decode(context, (uint256, address));

preCharge -= baseFee; // don't refund the base fee

uint256 _cachedPrice = updateCachedPrice(false);

// note: price is in native-asset-per-token increasing it means dividing it by markup

uint256 cachedPriceWithMarkup = _cachedPrice * DENOM / priceMarkup;

// Refund tokens based on actual gas cost

uint256 actualChargeNative = actualGasCost + tokenPaymasterConfig.refundPostopCost * actualUserOpFeePerGas;

uint256 actualTokenNeeded = weiToToken(actualChargeNative, cachedPriceWithMarkup);

if (preCharge > actualTokenNeeded) {

// If initially provided token amount is greater than the actual amount needed, refund the difference

SafeERC20.safeTransfer(token, userOpSender, preCharge - actualTokenNeeded);

} else if (preCharge < actualTokenNeeded) {

// Attempt to cover Paymaster's gas expenses by withdrawing the 'overdraft' from the client

// If the transfer reverts also revert the 'postOp' to remove the incentive to cheat

SafeERC20.safeTransferFrom(token, userOpSender, address(this), actualTokenNeeded - preCharge);

}

if (baseFee > 0) {

SafeERC20.safeTransfer(token, tokenPaymasterConfig.rewardsPool, baseFee);

}

emit UserOperationSponsored(userOpSender, actualTokenNeeded, actualGasCost, cachedPriceWithMarkup, baseFee);

refillEntryPointDeposit(_cachedPrice);

}

}

}

Looking at the code above, during validatePaymasterUserOp, the paymaster attempts to charge a maximum prefund amount first. This prefund is calculated by taking the gas limit specified in the UserOp and applying a markup price to convert the native ETH cost into the equivalent ERC20-token value. Later in postOp, the paymaster calculates the actual charge and refunds any excess from the prefund.

However, there is a critical oversight: the code does not account for gas penalties. The actual gas charged to the paymaster includes not just the gas used, but also any penalties incurred from differences between the execution gas limit and actual execution gas.

This vulnerability can be exploited by malicious users who set an artificially high gas limit to trigger the penalty. When penalties are applied, the paymaster will be charged significantly more than expected, potentially draining its funds since these additional costs were not factored into the calculation.

In fact, the bundler will be the one who receives the penalty paid by the paymaster. This means a bundler could submit their own UserOperation to be executed by themselves and profit if the penalty they can extract from the paymaster exceeds their own gas costs paid to the paymaster. In SEND's case, fortunately, because they operate their own bundler, any penalties incurred flow back to their controlled bundler, creating a closed economic loop that mitigates this particular attack vector.

Incorrect ERC-20 Handling

To improve user experience, some protocols introduced ERC-20 paymasters that allow users to pay transaction gas fees using ERC-20 tokens instead of native ETH (Just like what SEND did in the above code). The core concept is quite straightforward, the paymaster fronts the ETH gas costs to bundlers, then charges users an equivalent amount in ERC-20 tokens based on current market rates. However, implementing this token-to-ETH conversion and payment flow securely requires careful consideration.

Looking at the EntryPoint flow above, we can see that paymasters have two key interaction points during a UserOperation's lifecycle:

- During validation via

validatePaymasterUserOp() - After execution via

postOp()

This dual-interaction model has led to two predominant patterns for handling ERC-20 payments in paymaster implementations:

1. Pre-Payment with Refund Pattern

In this model, the paymaster requires users to pre-pay the maximum possible gas cost in ERC-20 tokens during validatePaymasterUserOp(). After execution completes, postOp() refunds any excess tokens based on actual gas consumed. This is analogous to how regular ETH gas payments work. Several protocols like SEND and Circle have implemented this approach. However, this pattern has one key disadvantage: users must first approve the paymaster to spend their ERC20 tokens before submitting any UserOperations. This additional setup step is required to ensure the paymaster can successfully deduct tokens before execution (specifically during validatePaymasterUserOp).

2. Post-Execution Charging Pattern

This alternative approach defers token collection until after execution. Instead of charging a prefund during validatePaymasterUserOp(), the actual token payment is calculated and collected in postOp() based on the exact gas consumed. At first glance, this appears to be the most user-friendly pattern since users can bundle their token approval transaction within the same UserOperation, eliminating the need for a separate pre-approval transaction before submitting the UserOp. This means users could interact with the paymaster without any prior setup.

This approach used to work in EntryPoint version v0.6, but the pattern no longer works in v0.7. In fact, using this pattern can lead to loss of funds for the paymaster. Let's take a closer look at how v0.7 handles the execution phase:

function _executeUserOp(

uint256 opIndex,

PackedUserOperation calldata userOp,

UserOpInfo memory opInfo

)

internal virtual

returns (uint256 collected) {

[...]

bool success;

{

[...]

if (methodSig == IAccountExecute.executeUserOp.selector) {

bytes memory executeUserOp = abi.encodeCall(IAccountExecute.executeUserOp, (userOp, opInfo.userOpHash));

innerCall = abi.encodeCall(this.innerHandleOp, (executeUserOp, opInfo, context));

} else

{

innerCall = abi.encodeCall(this.innerHandleOp, (callData, opInfo, context));

}

assembly ("memory-safe") {

success := call(gas(), address(), 0, add(innerCall, 0x20), mload(innerCall), 0, 32)

collected := mload(0)

}

_restoreFreePtr(saveFreePtr);

}

if (!success) {

[...]

if (innerRevertCode == INNER_OUT_OF_GAS) {

// handleOps was called with gas limit too low. abort entire bundle.

// can only be caused by bundler (leaving not enough gas for inner call)

revert FailedOp(opIndex, "AA95 out of gas");

} else if (innerRevertCode == INNER_REVERT_LOW_PREFUND) {

// innerCall reverted on prefund too low. treat entire prefund as "gas cost"

uint256 actualGas = preGas - gasleft() + opInfo.preOpGas;

uint256 actualGasCost = opInfo.prefund;

_emitPrefundTooLow(opInfo);

_emitUserOperationEvent(opInfo, false, actualGasCost, actualGas);

collected = actualGasCost;

} else {

[...]

collected = _postExecution(

IPaymaster.PostOpMode.postOpReverted,

opInfo,

context,

actualGas

);

}

}

}

During execution, the EntryPoint contract makes a call to its own innerHandleOp function through a low-level call(). This is done to create a new call context for executing the user operation.

If this call fails (when success is false), the code enters an error handling flow that checks the innerRevertCode. There are three possible paths:

- If

innerRevertCodeisINNER_OUT_OF_GAS, it means the bundler didn't provide enough gas for execution. This causes the entire bundle to fail with"AA95 out of gas". - If

innerRevertCodeisINNER_REVERT_LOW_PREFUND, it means the user didn't prefund enough gas. In this case, it charges the entire prefund amount as gas cost. - For any other revert reason, the code will still call

_postExecution()but withPostOpMode.postOpReverted. This ensures proper cleanup happens even on failure.

We're particularly interested in the third error path, where innerRevertCode is neither INNER_OUT_OF_GAS nor INNER_REVERT_LOW_PREFUND. To understand this case better, let's examine how innerHandleOp works.

function innerHandleOp(

bytes memory callData,

UserOpInfo memory opInfo,

bytes calldata context

) external returns (uint256 actualGasCost) {

[...]

IPaymaster.PostOpMode mode = IPaymaster.PostOpMode.opSucceeded;

if (callData.length > 0) {

bool success = Exec.call(mUserOp.sender, 0, callData, callGasLimit);

if (!success) {

uint256 freePtr = _getFreePtr();

bytes memory result = Exec.getReturnData(REVERT_REASON_MAX_LEN);

if (result.length > 0) {

emit UserOperationRevertReason(

opInfo.userOpHash,

mUserOp.sender,

mUserOp.nonce,

result

);

}

_restoreFreePtr(freePtr);

mode = IPaymaster.PostOpMode.opReverted;

}

}

unchecked {

uint256 actualGas = preGas - gasleft() + opInfo.preOpGas;

return _postExecution(mode, opInfo, context, actualGas);

}

}

We observe that, in the happy path, innerHandleOp is expected to not only execute the actual UserOperation call, but also call _postExecution. This means that the third failure handling path, which passes postOpReverted as its mode, happens when something goes wrong with the _postExecution call inside innerHandleOp.

Let's examine the _postExecution code to understand where the revert might occur.

function _postExecution(

IPaymaster.PostOpMode mode,

UserOpInfo memory opInfo,

bytes memory context,

uint256 actualGas

) internal virtual returns (uint256 actualGasCost) {

[...]

if (paymaster == address(0)) {

refundAddress = mUserOp.sender;

} else {

refundAddress = paymaster;

if (context.length > 0) {

actualGasCost = actualGas * gasPrice;

uint256 postOpPreGas = gasleft();

if (mode != IPaymaster.PostOpMode.postOpReverted) {

try IPaymaster(paymaster).postOp{

gas: mUserOp.paymasterPostOpGasLimit

}(mode, context, actualGasCost, gasPrice)

// solhint-disable-next-line no-empty-blocks

{} catch {

bytes memory reason = Exec.getReturnData(REVERT_REASON_MAX_LEN);

revert PostOpReverted(reason);

}

}

// Calculating a penalty for unused postOp gas

// note that if postOp is reverted, the maximum penalty (10% of postOpGasLimit) is charged.

uint256 postOpGasUsed = postOpPreGas - gasleft();

postOpUnusedGasPenalty = _getUnusedGasPenalty(postOpGasUsed, mUserOp.paymasterPostOpGasLimit);

}

}

[...]

}

It turns out that if the postOp() call fails, it will revert with PostOpReverted. However, as we can see in the previous code of _executeUserOp, even though innerHandleOp fails, the execution won't revert. Instead, it will continue to make another _postExecution call with postOpReverted mode, and it won't try to call postOp() again. This means the bundler still gets paid for submitting the failed UserOperation.

Now that we understand this behavior where postOp() is allowed to fail while the bundler still gets paid, let's examine a real-world example from the most widely used paymaster currently, which is the paymaster implemented by Pimlico.

function _postOp(

PostOpMode, /* mode */

bytes calldata _context,

uint256 _actualGasCost,

uint256 _actualUserOpFeePerGas

)

internal

{

ERC20PostOpContext memory ctx = _parsePostOpContext(_context);

uint256 expectedPenaltyGasCost = _expectedPenaltyGasCost(

_actualGasCost, _actualUserOpFeePerGas, ctx.postOpGas, ctx.preOpGasApproximation, ctx.executionGasLimit

);

uint256 actualGasCost = _actualGasCost + expectedPenaltyGasCost;

uint256 costInToken =

getCostInToken(actualGasCost, ctx.postOpGas, _actualUserOpFeePerGas, ctx.exchangeRate) + ctx.constantFee;

uint256 absoluteCostInToken =

costInToken > ctx.preFundCharged ? costInToken - ctx.preFundCharged : ctx.preFundCharged - costInToken;

SafeTransferLib.safeTransferFrom(

ctx.token,

costInToken > ctx.preFundCharged ? ctx.sender : ctx.treasury,

costInToken > ctx.preFundCharged ? ctx.treasury : ctx.sender,

absoluteCostInToken

);

uint256 preFundInToken = (ctx.preFund * ctx.exchangeRate) / 1e18;

if (ctx.recipient != address(0) && preFundInToken > costInToken) {

SafeTransferLib.safeTransferFrom(ctx.token, ctx.sender, ctx.recipient, preFundInToken - costInToken);

}

emit UserOperationSponsored(ctx.userOpHash, ctx.sender, ERC20_MODE, ctx.token, costInToken, ctx.exchangeRate);

}

As shown above, the paymaster calculates the actual gas used and attempts to charge the user by calling safeTransferFrom. Note that preFundCharged can be zero, as users can opt out of any preFund during the validation phase. If the user hasn't given sufficient allowance to Pimlico's paymaster for the transfer, the postOp call inside innerHandleOp will revert and the paymaster won't be able to collect payment from the user.

However, even when postOp fails, the EntryPoint will still complete the execution and pay the bundler who submitted it. Importantly, this payment comes from the paymaster's deposit, since during validation the requiredPrefund was taken from the paymaster's deposit.

This creates a critical vulnerability for paymasters that implement post-execution charging patterns. Even if the postOp call fails (meaning the paymaster couldn't collect payment from the user), the paymaster still has to pay the bundler's gas costs from their deposited funds. This vulnerability can be exploited by malicious bundlers in the following way:

- The bundler creates a

UserOperationwith an intentionally highgasPrice - The bundler ensures the

postOpcall will fail by revoking the paymaster's token allowance beforepostOpexecutes - When

postOpfails, the bundler still gets paid their high gas costs by the paymaster - The paymaster loses money since they paid the bundler but couldn't collect from the user

- The bundler profits as long as their actual gas costs are less than what they charged

This effectively allows bundlers to drain paymaster deposits by submitting UserOperations designed to fail during postOp while maximizing the gas costs they can charge to the paymaster.

Some paymasters try to protect against this by simulating the UserOperation execution before signing and allowing it to be submitted. However, this protection can be easily bypassed because an attacker can simply approve the required token allowance during simulation to pass validation, but then revoke the allowance just before the UserOperation is submitted via handleOps. This means the postOp will pass simulation but fail during actual execution, allowing the bundler to drain the paymaster's deposit from the EntryPoint.

To protect against this vulnerability, paymasters should implement pre-execution charging patterns rather than post-execution charging. This means requiring users to pre-fund the full estimated gas cost during the validation phase, before the operation executes. By collecting payment upfront, the paymaster is protected against failed post-execution transfers that could be exploited by malicious bundlers.

If post-execution charging is absolutely necessary for UX reasons, paymasters have several mitigation strategies available. One approach is to restrict usage to a whitelist of trusted bundlers, though this introduces centralization concerns. Alternatively, Pimlico tries to address this issue by tightening API limits and constraining ERC-20 usage for its users.

The most secure approach is to require upfront pre-funding, even though it may temporarily lock more user funds. This small UX tradeoff is worth the strong security guarantees it provides against paymaster exploitation.

Conclusion

ERC-4337 paymasters enable powerful new UX patterns by abstracting away gas costs from end users. However, implementing them securely requires careful consideration of the standard's execution flow and potential attack vectors. The key lessons are:

- Always collect full payment during validation, not after execution

- Be conservative with gas estimations and include safety margins

- Carefully validate all user inputs and token transfers

- Test extensively, including simulation of malicious behavior

- Always review changes in new

EntryPointversions, as they may impact your paymaster's design and security assumptions

The last point is particularly important as the ERC-4337 standard continues to evolve. Changes to the EntryPoint contract's behavior could potentially break existing paymaster implementations or introduce new security considerations. Developers should thoroughly review release notes and diffs when upgrading to new EntryPoint versions.

By following these best practices, developers can build robust paymasters that enhance UX while protecting against exploitation. As the ERC-4337 ecosystem matures, secure paymaster implementations will be crucial for driving mainstream adoption of account abstraction.

If you're building a paymaster and want to ensure it's secure against these and other vulnerabilities, consider getting an audit from us. Our team has extensive experience auditing ERC-4337 implementations and can help identify potential security issues before they impact production.